Meat Loaf, ‘Bat out of Hell’ rock superstar, dies at 74

]

]

NEW YORK (AP) — Meat Loaf, the heavyweight rock superstar loved by millions for his “Bat Out of Hell” album and for such theatrical, dark-hearted anthems as “Paradise By the Dashboard Light,” “Two Out of Three Ain’t Bad,” and “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That),” has died. He was 74.

The singer born Marvin Lee Aday died Thursday, according to a family statement provided by his longtime agent Michael Greene.

“Our hearts are broken to announce that the incomparable Meat Loaf passed away tonight,” the statement said. “We know how much he meant to so many of you and we truly appreciate all of the love and support as we move through this time of grief in losing such an inspiring artist and beautiful man… From his heart to your souls… don’t ever stop rocking!”

No cause or other details were given, but Aday had numerous health scares over the years.

“Bat Out of Hell,” his mega-selling collaboration with songwriter Jim Steinman and producer Todd Rundgren, came out in 1977 and made him one of the most recognizable performers in rock.

Fans fell hard for the roaring vocals of the long-haired, 250-plus pound singer and for the comic non-romance of the title track, “You Took The Words Right Out of My Mouth,” “Two Out of Three Ain’t Bad” and “Paradise By the Dashboard Light,” an operatic cautionary tale about going all the way.

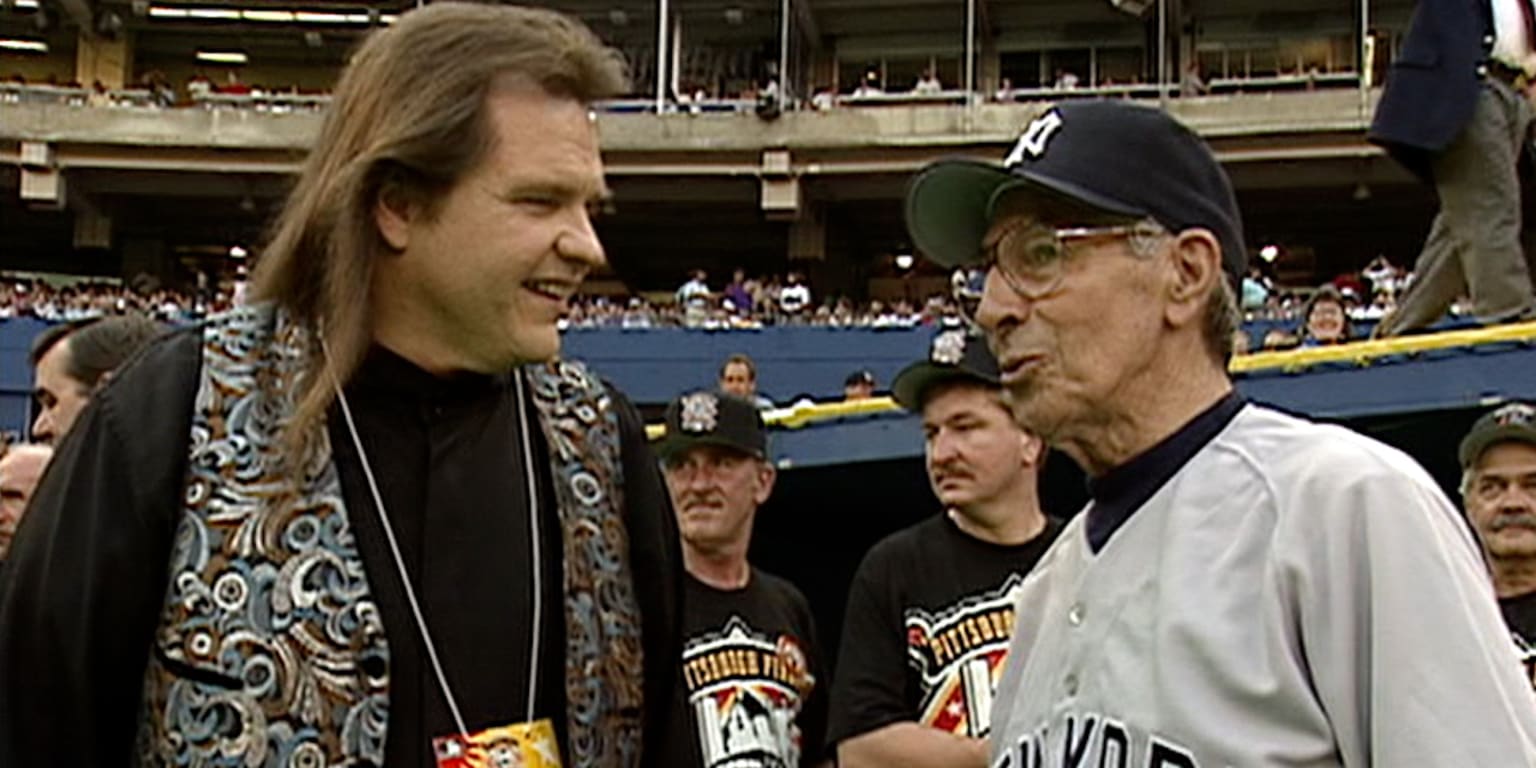

“Paradise” was a duet with Ellen Foley that featured play-by-play from New York Yankees broadcaster Phil Rizzuto, who alleged — to much skepticism — that he was unaware of any alternate meanings to reaching third base and heading for home.

After a slow start and mixed reviews, “Bat Out of Hell” became one of the top-selling albums in history, with worldwide sales of more than 40 million copies. Meat Loaf wasn’t a consistent hit maker, especially after falling out for years with Steinman. But he maintained close ties with his fans through his manic live shows, social media and his many television, radio and film appearances, including “Fight Club” and cameos on “Glee” and “South Park.”

Friends and fans mourned his death on social media. “I hope paradise is as you remember it from the dashboard light, Meat Loaf,” actor Stephen Fry said on Twitter. Andrew Lloyd Webber tweeted: “The vaults of heaven will be ringing with rock.” And Adam Lambert called Meat Loaf: “A gentle hearted powerhouse rock star forever and ever. You were so kind. Your music will always be iconic.”

Meat Loaf’s biggest musical success after “Bat Out of Hell” was “Bat Out of Hell II: Back into Hell,” a 1993 reunion with Steinman that sold more than 15 million copies and featured the Grammy-winning single “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That).”

Steinman died in April.

Aday’s other albums included “Bat Out of Hell III: The Monster is Loose,” “Hell in a Handbasket” and “Braver Than We Are.” His songs included “Dead Ringer for Love” with Cher and she shared on Twitter that she “had so much fun” on the duet. “Am very sorry for his family, friends and fans.”

A native of Dallas, Aday was the son of a school teacher who raised him on her own after divorcing his alcoholic father, a police officer. Aday was singing and acting in high school (Mick Jagger was an early favorite, so was Ethel Merman) and attended Lubbock Christian College and what is now the University of North Texas. Among his more notable childhood memories: Seeing John F. Kennedy arrive at Love Field in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963, then learning the president had been assassinated and driving to Parkland Hospital and watching a bloodied Jackie Kennedy step out of a car.

He was still a teenager when his mother died and when he acquired the nickname Meat Loaf, the alleged origins of which range from his weight to a favorite recipe of his mother’s. He left for Los Angeles after college and was soon fronting the band Meat Loaf Soul. For years, he alternated between music and the stage, recording briefly for Motown, opening for such acts as the Who and the Grateful Dead and appearing in the Broadway production of “Hair.”

By the mid-1970s, he was playing the lobotomized biker Eddie in the theater and film versions of “The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” had served as an understudy for his friend John Belushi for the stage production of National Lampoon and had begun working with Steinman on “Bat Out of Hell.” The dense, pounding production was openly influenced by Wagner, Phil Spector and Bruce Springsteen, whose bandmates Roy Bittan and Max Weinberg played on the record. Rundgren initially thought of the album as a parody of Springsteen’s grandiose style.

Steinman had known Meat Loaf since the singer appeared in his 1973 musical “More Than You Deserve” and some of the songs on “Bat Out of Hell,” including “All Revved Up With No Place to Go,” were initially written for a planned stage show based on the story of Peter Pan. “Bat Out of Hell” took more than two years to find a taker as numerous record executives turned it down, including RCA’s Clive Davis, who disparaged Steinman’s songs and acknowledged that he had misjudged the singer: “The songs were coming over as very theatrical, and Meat Loaf, despite a powerful voice, just didn’t look like a star,” Davis wrote in his memoir, “The Soundtrack of My Life.”

With the help of another Springsteen sideman, Steve Van Zandt, “Bat Out of Hell” was acquired by Cleveland International, a subsidiary of Epic Records. The album made little impact until months after its release, when a concert video of the title track was aired on the British program the Old Grey Whistle Test. In the U.S., his connection to “Rocky Horror” helped when he convinced producer Lou Adler to use a video for “Paradise By the Dashboard Light” as a trailer for the cult movie. But Meat Loaf was so little known at first that he began his “Bat Out of Hell” tour in Chicago as the opening act for Cheap Trick, then one of the world’s hottest groups.

“I remember pulling up at the theater and it says, ‘TONIGHT: CHEAP TRICK, WITH MEAT LOAF.’ And I said to myself, ‘These people think we’re serving dinner,’” Meat Loaf explained in 2013 on the syndicated radio show “In the Studio.”

“And we walk out on stage and these people were such Cheap Trick fans they booed us from the start. They were getting up and giving us the finger. The first six rows stood up and screamed… When we finished, most of the boos had stopped and we were almost getting applause.”

He is survived by Deborah Gillespie, his wife since 2007, and by daughters Pearl and Amanda Aday.

AP Entertainment Writer Andrew Dalton contributed from Los Angeles.

Copyright 2022 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Rizzuto struck platinum on Meat Loaf’s ‘78 hit

]

]

“OK, here we go, we got a real pressure cooker going here. Two down, nobody on, no score, bottom of the ninth. There’s the windup and there it is, a line shot up the middle. Look at him go, this boy can really fly! He’s rounding first and really turning it on now. He’s not letting up at all, he’s gonna try for second.

Meat Loaf saw himself as ‘revolutionising the idea of rock music into opera’, says Bob Harris

]

]

The UK first got a taste of Meat Loaf after The Old Grey Whistle Test music show aired the video for “Bat Out of Hell”. It caused a sensation.

He cemented his popularity when he appeared on the BBC2 programme in 1978 to perform “Paradise by the Dashboard Light” live.

Bob Harris, who presented the show at the time, described the performance as “energy-packed”.

Here he tells i what made Meat Loaf a success following the rock legend’s death, aged 74:

‘It was an incredible experience to see him play live’

“I was presenting The Old Grey Whistle Test and we got an advance copy of the video for Bat Out of Hell. We’d not really heard about Meat Loaf before.

“It was an amazing piece of work. Really dramatic stuff and because the music was so different and so powerful, we put it out on the show that following week and, I’m honestly not kidding, the reaction was unbelievable to this film.

“About two or three months later, he came and played a show at the Hammersmith Odeon, which I compèred, and he appeared on Whistle Test and played live. He did ‘Paradise By The Dashboard Light’.

“It was energy-packed. It was absolutely incredible. That was the breakthrough moment.

“He was working with various different female singers with whom he was playing out this very, very intimate relationship on stage. The vibe and atmosphere between Meat Loaf and Ellen Foley is just absolutely electric. And she completely bought into it… it was like a sort of five-minute piece of extraordinary theatre.

“He wasn’t making any pretence to be glamorous or anything like that. He was a big, sweaty man, bombing around the stage. It was really an incredible experience to see him play live.

“Although punk had arrived by now, it was still in the era of the big rock star. And he was so different from the big glamorous rock stars. He was a huge man at the time. He wore big white shirts with ruffles down the front and ruffled cuffs.

“He saw himself as this man who was kind of revolutionising the idea of rock music into opera, almost. He took rock to a very operatic place – even bigger than ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ in that respect. It really did add layers and layers to what we always thought of as being rock music. It added a cinematic element to it all, very visual.

“He was a huge character. He was loud. He took over a room and I think that’s what I most remember about spending time with him, that he was in charge of his moment. He drew attention to himself, but that’s what he wanted to do.

“[Songwriter and composer] Jim Steinman validated what Meat Loaf was. Didn’t just validate it, he emphasised it, made it bigger.

“I think Jim Steinman was a bit of a genius, the way he was able to manipulate existing sayings or thoughts or cliches into song titles that people would remember.”

Understanding Meat Loaf through the lens of an 8 year old

]

]

The album cover was scary, exciting, and somehow loud. A motorcycle, adorned with a cow skull in the front and white exhaust or possibly flame behind it, soared through the air. A demon bat screeched in the distance. The rider, a muscled-man with distinct Valkyrie undertones, hangs on for dear life in a pose I wouldn’t understand the undertones behind until much, much later.

It’s Meat Loaf’s Bat Out of Hell, and it’s sitting on the dining room table. My dad is carefully studying the back, just like he has roughly twice a week for as long as I can remember. He is wearing headphones that cover 60 percent of his head. They are connected to a knockoff Japanese stereo through a cord thicker than the one that kept our telephone attached to its receiver.

I am 8 years old and ready to depart to the TV room for Friday night’s TGIF lineup — Family Matters, Full House, Step-by-Step, the works. But first I’ve got to finish chores, which means clearing the dishes from the table. Dad didn’t really drink back then. Didn’t smoke, either. His deliverance came 46 minutes, 25 seconds at a time, beginning with the title track and slipping through operatic anthems, power ballads and the song he’d play all eight-plus minutes of at my sister’s wedding; Paradise by the Dashboard Light.

That’s where he’s landed tonight, having already hummed and bobbed his head through You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth. His voice rose a level to sing the chorus of Two Out of Three Ain’t Bad, betraying the subtle sadness behind a man who was Henny Youngman levels of prolific when it came to dad jokes. But when Paradise came on — those first 11 notes screeching out of Jim Steinman’s glorious, drama-kid brain and through a perfectly scratchy electric guitar — it sent lightning through his body.

His eyes closed. His shoulders shook. Every word of those lyrics, every syllable, tumbled from his lips in perfect sync with the record spinning in the background we couldn’t hear. He sang with the conviction of a born-again sinner on a Sunday morning.

Well I remember every little thing, as if it happened only yesterday,

Parking by the lake and there was not another car in sight…

The whole family knew the song well. Our summer vacations were two-week trips to visit family in Pittsburgh. Each way was a 10-hour drive with a handful of cassettes and a portable tape player rested on the front console armrest. The only one that really got played was a homemade mix barely labeled on a blank Maxell. It had some Bob Seger and Paul Evans and, for some reason, Memory from the musical Cats. It also had Paradise by the Dashboard Light on both the front and back sides.

Now Dad rose up from his seat as the chorus hit, a heavenly tilt upward before assuring the family he was both barely 17 as well as barely dressed. He gained steam as the song did, omitting nothing for me or my sister — who at 10 years older, understood at least slightly better than I did — as he sunk deeper into the world carefully created by Steinman and Loaf.

And now our bodies are oh so close and tight,

It never felt so good, it never felt so right

And we’re glowing like the metal on the edge of a knife

I didn’t get any of that, but somehow, the piece that bothered me the most was the knife. Knives didn’t glow, and if they did it certainly just wouldn’t be one sliver that found the light. But a clumsy metaphor was, in fact, the perfect parallel to the clumsy everything going on behind it.

Besides, my dad was already onto the next beat, loudly proclaiming we were about to go all the way tonight. Then he doubled down toward the table, knowing he’d have to buy all the way in and save his breath to perfectly nail the next 52 seconds of breathless Phil Rizzuto play-by-play.

I narrowed my focus as well. Growing up a Red Sox fan in Rhode Island had conditioned me to baseball failure. It was the one part of the song I understood. I just wanted to know if this kid, the one that really makes things happen out there, was going to make it home or not. Every time I’d listen intently as though Ellen Foley wasn’t about to bring in Act III just in the nick of time.

Stop right there! I gotta know right now.

Yep, Dad did the lady parts too.

Do you love me? Will you love me forever?

Do you neeeeeed me? Will you nev-uh leave me?

Will you make me so happy for the rest of my life?

Will you take me away, will you make me your wife?

I gotta know right now, before we go any further:

Do you love me? Will you love me forever?

I didn’t realize this at the time, but this would be my sex education. Roughly five years later Dad, vastly underestimating my budding awkwardness and just how attractive the opposite sex would find my JV cross country body, sat me down for the talk. The center of a galaxy of bon mots USA TODAY would ultimately prefer not to have attached to its website was Paradise by the Dashboard Light. “Sex is a commitment, son. No one knows it better than me. No one said it better than Meat Loaf.”

At the table, however, I was watching a one-man ballet. His voice shifted back and forth like a veteran truck driver spinning around a wreck. His hands moved from accusing to pleading with the grace of a surgeon’s scalpel.

Foley’s parts were the actual knife in the song, slicing through five minutes of wallpapered happiness that preceded it. Meat Loaf begged in response. It was teenage trash Shakespeare, fed directly into one man’s brain and processed across 15 years and multiple worn-out copies of Bat out of Hell.

Then, the dam burst.

I couldn’t take it any longer, Lord I was crazed!

And when the feeling came upon me like a tidal wave

I started swearing to my god and on my mother’s grave

That I would love you to the end of time!

Dad hit every note with flooding relief and regret, coasting through the final minute-plus and to the end of the song. Then he’d get sucked back in to the album’s finale, For Crying Out Loud, and sing the full eight minutes, 45 seconds like a dirge. Eyes closed, slumped in a hard-back chair, a light sweat glowing as if he’d just done a quick workout.

Then he’d snap back to us, and inevitably I’d ask:

“Who’s that guy the baseball announcer was talking about?”

“That was Meat Loaf, too,” he’d respond.

“Was he safe at home?”

Then Dad paused, tilted his head, and scrunched his face a bit.

“He was. But he still lost.”

“But it was the bottom of the ninth, tie game!”

“Trust me, son. He lost.”

Forever No. 1: Meat Loaf’s ‘I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That)’

]

]

Forever No. 1 is a Billboard series that pays special tribute to the recently deceased artists who achieved the highest honor our charts have to offer — a Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 single — by taking an extended look back at the chart-topping songs that made them part of this exclusive club. Here, we honor the late Meat Loaf with a look at his first and only Hot 100 No. 1, the over-the-top 1993 epic ‘I’d Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That).’

Explore See latest videos, charts and news Jim Steinman Meat Loaf See latest videos, charts and news

Meat Loaf should’ve ruled the ’80s. His breakthrough album Bat Out of Hell had been one of the great success stories of the late ’70s, a fully formed debut that married prog-rock pomp with E Street Band urgency and operatic stakes, carried by the actor/singer’s larger-than-life voice and personality. It sold tens of millions of copies worldwide, reached the year-end Billboard 200 albums charts for both 1978 and 1979, and made Meat Loaf a superstar. The next decade would see pop and rock only further embracing Bat Out of Hell’s sense of over-the-top melodrama, while the 1981 introduction MTV gave popular music’s most visually and theatrically inclined artists a platform to present their widescreen visions to the world in heavy rotation. Everything was set up for the artist born Marvin Lee Aday to become one of the defining artists of the era.

However, Meat Loaf’s attempts to follow up Bat Out of Hell were unfortunately waylaid. At the end of the decade, the singer lost his voice due to a combination of tour exhaustion and drug abuse, and primary artistic partner and songwriter Jim Steinman decided to use the songs he’d penned for the project for his own debut album as a performer, 1981’s Bad For Good. By the time singer and songwriter reconvened for the Dead Ringer album later that year, public enthusiasm had dimmed and the material wasn’t as strong — especially without Bat producer, ’70s hitmaker and Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Todd Rudngren, behind the boards — leading to the set peaking at No. 45 on the Billboard 200 and generating no major hits. Meat Loaf and Steinman’s professional relationship would splinter shortly after, and while the latter would pen sizable smashes that decade for Bonnie Tyler (“Total Eclipse of the Heart”) and Air Supply (“Making Love Out of Nothing at All” — both of which Loaf claims were originally offered to him — the singer would go the rest of the ’80s without so much as a top 40 Billboard Hot 100 hit or RIAA gold-certified album, seemingly a has-been in the decade he helped set the table for.

By late 1993, the ’90s were already, well, the ’90s. The crescendoing grandiosity of the ’80s had largely faded out in popular music, with the joint takeovers of grunge and alternative in rock and West Coast G-funk and East Coast boom-bap in rap making the decade’s musical identity simpler, edgier, and significantly less fantastical. The biggest top 40 stars were in the pop/R&B hybrid hitmaking mold of Mariah Carey and Janet Jackson. It would not have seemed like the ideal time for Meat Loaf, once again reunited with Steinman and ready to journey Back Into Hell with the long-delayed official sequel to his 1977 blockbuster. But journey the pair did, and the singer was rewarded with the first and only Hot 100 No. 1 of his career, thanks to the set’s return-to-form lead single — the epic-even-when-radio-edited “I’d Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That).”

In truth, Meat Loaf’s return wasn’t totally without precedent or peer, even in 1993. That was the year that Aerosmith, fellow ’70s rock survivors who’d since fallen on hard times — albeit ones who had started their comeback a little earlier, returning to pop prominence in the late ’80s — started enjoying their greatest success of the MTV era, with their multi-platinum Get a Grip album and a trio of plot- and action–heavy videos starring teen actress Alicia Silverstone. It was also the final year of Guns N’ Roses’ Use Your Illusion cycle, when the once raw and raunchy hard-rock band got big and weird, culminating in the nine-minute psychodrama of “Estranged” and its music video, one of the most epic and expensive (if also largely inscrutable) clips ever aired on MTV. There was still counter-programming available for those who missed the large-scale, panoramic rock renderings of the late ’70s and ’80s — and Meat Loaf was prepared to give it to ’em bigger and more colorfully than anyone.

As the opening track and lead single to Bat Out of Hell II: Back Into Hell, “I’d Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That)” makes its intentions clear right away, with guitar chopped up and distorted to sound like a revving motorcycle — like the one on the Bat cover — giving way to a downpour of dramatic piano plinks (which starts the song’s radio edit) and crashing guitar and drums. Soon, the singer appears, launching right into the song’s chorus: “And I would do anything for love/ I’d run right into hell and back/ I would do anything for love/ I’ll never lie to you and that’s a fact/ But I’ll never forget the way you feel right now, oh no, no way/ And I would do anything for love, but I won’t do that.” (That the first lyric you hear on the song is “And” really makes it seem like Meat Loaf is picking up right where he left off 17 years ago, with the two eras barely even separated by an ellipsis.)

Despite coming so strong out of the gate, “I’d Do Anything For Love” still has a ways to go. The full album version is a staggering 12 minutes long, while the edited MTV version runs a somewhat more manageable 7:40 and the radio edit gets in and out in a brisk-by-comparison 5:16. As was typical of classic Meat Loaf, there are a variety of shifts in tempo, tone and intensity — and, in an echo of Ellen Foley duet (and signature Bat hit) “Paradise By the Dashboard Light,” a female co-star in studio singer Lorraine Crosby, though on the album version she doesn’t even enter until almost the 9:30 mark. But it always circles back to that immediately unforgettable chorus, a pledge of eternal and unconditional devotion — well, except for one lone condition.

And what was that exception? The mystery behind the “That” in “I’d Do Anything For Love (But I Won’t Do That)” certainly played a large part in making the song a phenomenon, a common subject of casual listener debate that lingers to this day. (The 2020 Oscar-nominated drama The Sound of Metal features its two main characters — metal bandmates and romantic partners — singing along to the song while driving and trying to divine the “That” meaning, with one quipping, “Anal.”) In truth, the mystery was no mystery at all: As Meat Loaf would frequently point out, often seemingly to his great frustration, the answer is laid plain in that opening chorus, and again (with different but similarly themed lyrics) in every subsequent chorus: “I’ll never forget the way you feel right now… I would do anything for love, but I won’t do that.” (Talking to journalist Dan Reilly, Loaf blamed Steinman’s writing for hammering home the “I would do anything for love” part of the chorus with so much repetition that listeners always forgot the lyrics that came immediately before it.)

Regardless of the reason for the confusion, the seeming ambiguity of the chorus helped make the song a mid-’90s pop culture fixture — as of course, did the song’s video, directed by future action feature auteur Michael Bay. A Beauty and the Beast-themed love story featuring Meat Loaf in monster makeup and actress Dana Patrick in Lorraine Crosby’s co-starring role — with heavy visual echoes of Aerosmith’s “Janie’s Got a Gun” and the GnR Illusion mini-epics (and no shortage of motorcycles, natch) — the clip finally brought Meat Loaf fully to life on MTV, as none of his ’80s clips had been able to do. It briefly made the then-46-year-old singer as big a star on the channel as Eddie Vedder or Snoop Doggy Dogg, finishing at No. 11 on the channel’s top 100 videos of the year list for 1993.

While the singles on the original Bat Out of Hell may have ultimately proven too unwieldy to threaten the top of the Hot 100 — proto-power ballad “Two Out of Three Ain’t Bad” was the album’s biggest hit, peaking at No. 11, while “Paradise” and “You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth” scraped the bottom of the top 40 — the pop mainstream seemed to have no such concerns in embracing “I’d Do Anything For Love.” The song debuted on the Hot 100 at No. 68 on the chart dated Sept. 16, 1993; a mere seven weeks later, it replaced Mariah Carey’s “Dreamlover” at the chart’s apex, staying there for five weeks before being booted by Janet Jackson’s “Again,” a rare rock detour in a year where the Hot 100 was largely dominated by pop and R&B. In 1994, it also won Meat Loaf his lone Grammy, for best rock vocal performance, solo.

Meat Loaf never reached the chart’s top 10 again, though he did notch two more top 40 hits off Bat II in 1994 with “Rock and Roll Dreams Come Through” (No. 13) and “Objects in the Rear View Mirror May Appear Closer Than They Are” (No. 38), and made one final visit to the region in 1995 with Welcome to the Neighborhood lead single “I’d Lie For You (And That’s the Truth).” Steinman would return to the chart’s top tier in 1996 with the Celine Dion-sung, No. 2-peaking “It’s All Coming Back to Me Now” — another stadium-sized power ballad whose sound (and music video) were deeply reminiscent of “Anything For Love.” Loaf and Steinman together would try to recapture the Bat magic one more time a decade later, with 2006’s Bat Out of Hell III: The Monster Is Loose, which debuted in the top 10 of the Billboard 200 but received mixed reviews and failed to generate a hit single.

Today, the original Bat Out of Hell is the work most closely associated with Meat Loaf, still inescapable on classic rock radio and at karaoke nights and inspiring its own (Steinman-helmed) theatrical adaptation in 2017. But “Anything For Love” stands alone as Meat Loaf’s global pop peak — going to No. 1 in over two dozen countries, restoring the rock icon’s legacy, and making up for nearly his entire lost ’80s with one super-sized single.